By Amanda Iacone, Reporter at Bloomberg Tax | Originally posted on: news.bloombergtax.com

- New lease accounting rules short-change comparability between international and U.S. companies

- Data vendors, companies adjusting the universal metric for lease accounting

The corporate earnings measurement known as EBITDA stormed into popular use during the leverage buyout boom of the 1980s, as investors looked for a measure better than net income to figure out how much cash a company generated, and ultimately whether it could handle its debt.

In the decades since, it evolved into a tool for evaluating everything from credit strength to equity multiples even as it was derided as “earnings before expenses” and came under scrutiny at the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Now, sweeping changes to lease accounting rules instituted this year have delivered a blow to the relevance of earnings before taxes, depreciation and amortization as the metric has been used traditionally. Differences in methods used to calculate it already limited its usefulness, said Robert Schiffman, a Bloomberg Intelligence credit research analyst, “and these accounting issues just make it a little bit more imperfect.”

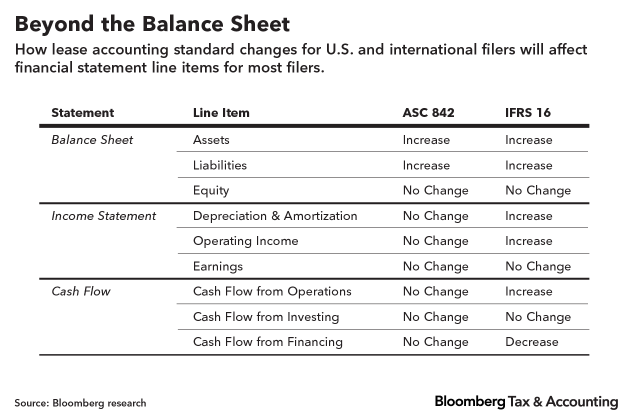

The new rules for lease accounting required companies to report all long-term leases on their balance sheets for the first time.

The trillions of dollars’ worth of operating leases for airplanes, retail space, and office equipment were long estimated by investors and ratings agencies. But the accounting change triggered a few surprises for investors because, while instituted as a step toward balance sheet honesty, it also impacted earnings for such companies as Ryder System Inc., Duke Realty Corp., and Darden Restaurants Inc.

The new rules also boosted international filers’ EBITDA, making their operating performance look better than most of their U.S. competitors. Comparing companies’ performance metrics to prior periods also poses challenges for analysts because earlier figures aren’t being restated. And some companies and data providers are adjusting the measurement to counter the accounting, in ways that may not be transparent to investors.

“If you’re not aware of these changes, you could get caught off guard,” said Ron Graziano,accounting & tax research analyst at Credit Suisse LLC. “Even if you are aware of these changes, as an investor, you might not be aware of how they might be flowing into commonly used metrics that you are relying on whether it be EBITDA, whether it be enterprise value, leverage metrics, even PP&E (property, plant and equipment assets).”

Split Personality

Differences in EBITDA among international and U.S. companies stem from dueling accounting treatments for finance and operating leases.

In the U.S., the Financial Accounting Standards Board retained both types of leases and limited the impact to the income statement and cash flows. The International Accounting Standards Board opted to treat all leases as finance leases.

Companies with finance leases will record interest and amortization expense, which directly feed into EBITDA. Interest is typically higher earlier on and will decrease over time—that means higher costs and reduced earnings initially compared to the straight-lined rental expenses most U.S. companies will report. EBITDA for companies with finance leases excludes actual rent payments, a major operating cost for many companies that now has to be counted.

And that’s where the problem lies. The balance sheet impact is the same for both accounting models, but international companies could see a reduction to net income—and a higher EBITDA compared to U.S. companies, Graziano said.

Don’t Forget the Rent

Data providers have struggled with how to present EBITDA in a way that would to help global investors compare companies across regions and time, Graziano said.

Bloomberg L.P., for example, treats U.S. companies’ operating leases as if they were finance leases and adds back rental expense to EBITDA to provide a globally comparable figure.

A similar version of the metric, known as EBITDAR, offers investors a better number to compare today, Graziano said.

Other vendors may use different methods to calculate the commonly used figure. Companies too have made adjustments to their reported versions to account for the new leasing standard.

Some analysts may come up with their own version—like revenue minus the costs of goods sold. The bottom line is there is no standard formula for calculating EBITDA, said Janet Pegg, an analyst with Zion Research Group.

All the confusion has frustrated not just investors, but management too.

AMC Entertainment Holdings Inc. CEO Adam Aron blamed the data changes for the drop in the theater owner’s stock price, culminating in a 52-week low in early July, after it unveiled its new balance sheet laden with $5.4 billion in operating lease liabilities in May.

Changes to how the data providers present debt also made AMC appear to be “wildly over-leveraged and AMC shares became “stunningly expensive” even though the new accounting didn’t affect its cash or interest due, Aron said during an Aug. 8 earnings call.

In a 16-page disclosure issued in April, the company said the new rules would have reduced its adjusted EBITDA by $93 million in 2018 and would have little impact on reported net income. Its first quarter 2019 adjusted EBITDA dropped from the year before reflecting in part a $22.7 million impact from the new accounting.

AMC’s stock price has yet to return to the $13.63 it was on the day of the May disclosure.

Aron urged investors to exclude operating leases from debt calculations when comparing to the company’s adjusted EBITDA. Otherwise, add back rent expense, he said.

EBITDA by Any Other Name

Unlike AMC, Nordstrom Inc. and Iron Mountain Inc. each reported that the new lease accounting rules dragged down their adjusted versions of the metric. Nordstrom said the rules would reduce its EBITDAR by $176 million over its 2019 fiscal year. Iron Mountain, in its annual earnings report, said full-year adjusted EBITDA would be down $10 million to $15 million in 2019.

Still, not all companies provide EBITDA to investors—it’s the fourth most commonly used metric among companies in the S&P 500, according to an Audit Analytics analysis of earnings releases.

Some companies, like Amazon.com Inc., use free cash flow instead.

But increasingly, companies craft metrics unique to their business or industry. Adjusted net income, a more specific metric akin to EBITDA, is a popular alternative, said Scott Jones, a corporate securities lawyer with Pepper Hamilton LLP.

A recent crackdown by the Securities and Exchange Commission on the use of metrics other than generally accepted accounting principles has driven the shift away from EBITDA reporting, said Jones, who is also a certified public accountant.

The SEC permits the use of non-GAAP metrics, but with strings attached. Companies must justify why the metrics are useful. They also must reconcile the metrics against GAAP, provide consistent calculation and not mislead investors.

As companies sharpened their pencils, they realized maybe EBITDA wasn’t the best measure to provide, he said.

No Uniformity Here

Alterations that companies and data providers alike make to the metric is part of why it’s not reliable and not uniform across companies.

Often companies strip out stock compensation, and a laundry list of other costs. Instead, cash flow from operations should be investor’s “true north,” said Jack Ciesielski, an independent accounting analyst based in Baltimore.

Still, lease accounting adjustments alone are not likely to halt EBITDA.

“It’s the cockroach of metrics,” Ciesielski said. “It’ll always be around; you can’t kill it. As long as people want a shortcut, they’ll be using EBITDA or some form of it.”

Originally posted on: news.bloombergtax.com